Editor’s Note: We thought you’d like to read a remarkable presentation by our Executive Director, Maurice Middleberg. Our thanks to St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church in Boca Raton, Florida for inviting Free the Slaves to spread the word about slavery today.

October 30, 2014

October 30, 2014

Ladies and gentlemen, good evening. Thank you so much for coming out tonight. It is a privilege to be with you.

I want to express my appreciation to Cassie Krejewski and Pam Campi for their support in making this evening’s event possible. I am especially grateful to Mary and Allan Springs for all their hard work and dedication in organizing this event.

Let me start with a quick word about Free the Slaves, the organization I am privileged to serve. We were founded in 2000. Our mission is to liberate those in slavery and change the conditions that allow slavery to persist. We currently have programs in Brazil, Haiti, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal and India. As I will explain during this talk, we believe that the keys to fighting slavery are educating and organizing at-risk communities; strengthening laws and law enforcement; and, ensuring impoverished communities have access to basic services.

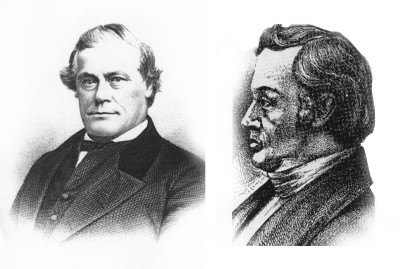

Elijah and Owen Lovejoy

Those of us engaged in the fight against modern day slavery are inheritors of a proud tradition. The two gentlemen you now see on the screen are Elijah and Owen Lovejoy. In the period before the American Civil War the two brothers were quite famous as leaders of the abolitionist movement. Both were deeply motivated by their Christian faith to seek freedom for enslaved people. Elijah published an anti-slavery newspaper, first in Missouri and then Illinois. In 1837, Elijah was murdered by a mob for persisting in his campaign against slavery. If you go to the Newseum in Washington, D.C., you will see a portrait of Elijah, who is considered the first martyr to a free press in America.

In 1857, Owen became a member of Congress, where he agitated ceaselessly against slavery. He was active in the Underground Railroad, helping to bring slaves to freedom. He worked closely with Abraham Lincoln to form the Republican Party. When Owen died in 1863, Lincoln said, “I have lost my closest friend in Congress.”

I tell you the story of these two men because we have with us tonight direct descendants of Owen and Elijah. Mary Springs is the great-great-great niece of Owen and Elijah. With Mary today are her sisters, Roberta and Fran. Mary and Roberta are also, I am proud to say, my sisters-in-law and Fran is my wife of 38 years. All three are continuing the family tradition by participating in the fight against slavery.

It is shocking that, more than 150 years later, slavery is not an historic relic. For tens of millions of people, it is the frightful, brutal reality of their lives.

Gold mine slavery in Ghana | Photo: FTS/Romano

Let me be clear what I mean by slavery.I don’t mean lousy wages or poor working conditions or a mean boss. I mean people who are held at a workplace against their will by violence or threat for purposes of sexual exploitation or forced labor so that other people can profit. We use the term slavery rather than trafficking because we want to be explicit about the conditions facing those we seek to serve.

Because slavery is a crime, it’s hard to get exact estimates of how many people are in this condition. The International Labor Organization puts the figure at 21 million; a more recent estimate by the Walk Free Foundation puts the number at 30 million. There seems little dispute that tens of millions of people are trapped in slavery.

While every country in the world is afflicted to some degree by slavery, it is more prevalent in some countries than others. The majority of slaves are Asia, especially the South Asian countries of India, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Sub-Saharan Africa is the other epicenter of slavery.

Child brick factory slavery in Pakistan | Photo: FTS/Mazhar

A quarter of those enslaved are children. The majority are women and girls. About a fifth of slavery is sexual slavery or forced prostitution. The remainder is in the private sector. Most slavery occurs in seemingly ordinary businesses – mines, farms, fishing boats, construction sites, stone quarries, brick kilns, carpet factories, and restaurants. Slavery is found wherever the products and services depend heavily on manual labor.

Those in slavery are ruthlessly exploited in hard, degrading and dangerous labor. I have seen with this my own eyes: girls and women victimized by sex trafficking; little girls used as domestic servants; little boys working on fishing boats; boys turned into child soldiers; women breaking rocks by hand in a stone quarry; men sent down primitive mine shafts in search of gold or rare minerals; and, entire families working as slaves for a loan shark over a debt that will never be paid off.

In the United States, the term trafficking almost automatically conjures images of sex trafficking. While this is a serious problem, it is important to understand that slavery manifests in many forms, all of which are versions of forcibly coercing the labor of a person for the profit of another. To fight slavery we must understand how it appears in different contexts in order to craft appropriate solutions. For that reason, all our programs begin with context-specific research so we understand how and why slavery is occurring in that setting.

What ties these different forms of slavery together is that the victims are held through force, fraud and coercion. They are not compensated for their work. They cannot leave. Their lives are plagued by extreme poverty and hardship. They live outside the redemptive powers of law, justice, mercy or common decency.

Slavery is big business. A recent report from the International Labor Organization estimates the profits from slave labor at $150 billion per year. It now ranks with drugs and arms trafficking as a major source of criminal revenue.

Pope Francis has said, “Human trafficking is an open wound on the body of contemporary society… It is a crime against humanity.”

How can this be? How can the ancient curse of slavery still exist? Most importantly, what will work in the fight against slavery?

Enslaved village in India | Photo: FTS/Middleberg

The photograph you now see is of a hamlet I visited in India. The dwellings are composed of cow dung, mud and thatch and have dirt floors. The inhabitants owned nothing more than a couple of pieces of crude, hand-made furniture. Running water and sanitation were unknown. There was no school for the children. People did not have access to health care. These low-caste Indians purportedly owed debts to the high caste landlord on whose property they lived. The landlord gave them just enough sustenance to keep working.

My Indian colleagues and I entered the village on foot. We had to hide to speak to the villagers. They told us that if the landlord or his agents saw them speaking to us without permission they would be beaten. One man said to me: “My father was a slave. I was born a slave. I don’t want to be a slave anymore. I don’t want my children to be slaves.”

What this example tells us is that slavery springs from vulnerability. While the vast majority of slaves are found among the poor of Asia and Africa, poverty alone does not explain slavery. Rather, slavery afflicts poor people who don’t have the tools to protect themselves.

Three factors are key: lack of awareness, lack of legal protection and the absence of basic services.

Lack of awareness of rights and risks is a critical vulnerability that can be addressed by educating and organizing at-risk communities like the one you see here.

For example, a common path to slavery is what is called debt bondage. People who encounter a financial crisis borrow money at an exorbitant rate. Since the debtor lacks cash to pay the loan, the lender demands that the debtor work off the loan on his farm, factory or mine. Of course, the loan can never really be paid off and the debt continues to accumulate and the borrower ends up perpetually enslaved. Worse yet, the debt becomes the responsibility of the entire the family and is inherited by the children, who are born into slavery. Part of the tragedy is the borrower doesn’t actually know that he or she is the victim of a crime; he or she actually believes the lender can demand labor until he deems the debt satisfied.

Similarly, people in impoverished rural areas are desperate for work and will believe the false promises of labor traffickers. We encounter this often in Nepal, where the trafficker will go into a village and say: “There is a good job for you in the big city or Malaysia or in one of the Gulf States. Just get in the truck and let me hold on to your passport until we get there.”

Brother Xavier Plassat organizes villagers in Brazil | Photo: FTS/Chernush

At Free the Slaves, we work with local grassroots organizations to educate vulnerable communities about their rights and the risks of trafficking. We use methods and messages that are appropriate to the local context. In the Congo, for example, we support the broadcasting of anti-slavery messages over a network of community radio stations. In Nepal, we work with local organizations to explain the risks of labor trafficking and how to migrate safely.

In this slide, you see Brother Xavier Plassat, who is the anti-slavery coordinator for the Pastoral Land Commission, one our partners in Brazil. Brother Xavier and the commission work with at-risk communities to educate them about the risks of labor trafficking, especially those associated with accepting offers to work in the lumber and charcoal operations in the Amazon jungle.

We work with communities to organize anti-slavery committees comprised of community members. In Nepal, they are called community vigilance committees. In Ghana, they are community child protection committees.

Ghana community child protection committee | Photo: FTS

The photos you see here are from Ghana, where community members meet to discuss child exploitation and enslavement. The committee members are given additional training and tools so they can act as a neighborhood watch against slavery. For example, the anti-slavery committee will draw up a list of the children in the village and track their whereabouts to be sure they are not engaged in forced labor. The committees also become the bridge to the police and other authorities to help secure protection for the community.

This process of educating and organizing people is enormously powerful. It is amazing to see the transformative effect that knowledge and collective action can have on a community. It is easy to prey upon the uneducated and disorganized. But an aware and cohesive community is a bulwark upon slavery.

One man in a small village in Haiti summed it up at a community meeting I attended when he said to me, “We were in darkness and now we are in light.”

Restavek domestic servitude slavery in Haiti | Photo: FTS/Linde

A second major vulnerability leading to slavery is lack of legal protection. In part, this reflects weak laws. In Haiti, one of the most widespread forms of slavery is known as restavek, a Creole word that means “stays with.” It is a perversion of an old custom, where poor families would send children to stay with wealthier relatives. In its current form, the children, most of whom are girls, become, like the girl shown here, household slaves who do the cleaning, cooking and child care. They are often sexually abused. Until very recently, there was no penalty in Haiti for keeping a child in forced domestic servitude.

The weakness of laws is often compounded by lax law enforcement. Police are often poorly trained and unaware of their own laws regarding slavery and trafficking. In other cases, corruption inhibits law enforcement.

We work with local organizations to advocate for better laws and improved law enforcement. In the case of Haiti, we helped a local coalition secure a new law that greatly increases the penalties for child slavery.

We train police and other government officials. We also train journalists to report on slavery, since public scrutiny makes it harder for police to turn a blind eye or collude with traffickers. In Brazil, we are supporting a group of young reporters to carry out investigative journalism focused on slavery. Brazil, to its great credit, has also established a specialized anti-slavery federal police squad.

Of course, we also work with local organizations and authorities to help liberate those in slavery. Sometimes this involves raids on work places. In other cases, emboldened communities will chase off the slaveholders and traffickers without external assistance.

Once liberated, survivors need help making the transition to a life in freedom. They are typically traumatized, often abused, almost invariably impoverished and may lack marketable skills. If they do not receive appropriate services they are, in fact, highly vulnerable to becoming re-enslaved. So it is important to help newly freed people get the services they need to reclaim their lives.

FTS ashram provides shelter for sex slavery survivors in India | Photo: FTS/FitzPatrick

In India, for example, we support an ashram that cares for girls and women who are victims of sex trafficking, which you see here. The girls range in age from about 8 to 20. They receive medical care, counseling, schooling and vocational training. Most of all, they are in a safe, caring and supportive environment.

During my most recent trip to India I happened to be visiting the ashram at the time of a local festival. It was inspiring and amazing to the girls playing, laughing and dancing; it was an incredible testament to the human spirit.

We also provide legal services to survivors so they can pursue restitution and agitate for prosecution of perpetrators.

Vulnerable communities typically lack access to basic services, especially schools, health care and credit. Out-of-school children are particularly vulnerable to being trafficked. The absence of affordable health care will generate a financial crisis that is exploited by traffickers. People go to loan sharks in the absence of legitimate sources of credit.

Working with our local partners, Free the Slaves helps at-risk communities gain access to these essential services. In the Congo for example, we work with our partners to help villages organize savings and loan groups so they don’t have to turn to loan sharks. When we can’t help directly, we build relations between the communities and other organizations or government agencies that can provide schooling, health care and credit. Increasing basic household security reduces the likelihood that a family will be exploited.

So these are they keys that open the locks of slavery: educate and organize at-risk communities; liberate and support those enslaved, while prosecuting perpetrators; and; promote household security through basic services.

We know this approach works. Last year, working with partners, Free the Slaves rescued over 3,100 people from slavery, helped almost 1,200 communities resist slavery, educated 18,500 people in villages about how to protect themselves from traffickers and trained over 1,500 government officials. Our efforts led to legal action against 105 slaveholders and traffickers.

Much more can be done. We can move from freeing thousands to tens and hundreds of thousands. But this will only happen if good people join the fight against slavery.

You now know the truth of slavery and how to stop it. Here is what you can do.

First, educate your families, friends and neighbors. Share the information you have acquired. Awaken those who might care. Enlist others to spread the word. There are cards available in the back of the room that will give you basic facts about slavery. More information is available on our web site, freetheslaves.net

Second, be careful consumers and investors. Remember that the products you buy or the companies in which you invest may be tainted by slavery on farms or mines or factories. Visit our website or KnowtheChain.org, which can give you information about whether companies are working keep slavery out of their products. Act on what you learn – let the companies you buy from and invest in know how you feel, either with praise for those with good practices or concern for those who don’t.

Third, be an advocate for good public policies. We need stronger laws, greater investment and more transparency to fight slavery. Sign up on our web site – freetheslaves.net – and support our advocacy for anti-slavery policies.

Lastly, I ask that you please become a donor to Free the Slaves. The work of freedom is not free. We need your help. I can’t afford to be coy about this. As a nonprofit organization, we depend solely on the generosity of our supporters to carry on the fight against slavery. There’s more information about Free the Slaves in the lobby and envelopes in which to place donations.

These images of Owen and Elijah symbolize the many thousands of Americans who took up the cause of freedom. I hope you will add your photo to the pantheon of heroes who worked to end slavery. My most fervent wish is that when the great-grandchildren of Mary, Roberta and Fran come back to St. Joan slavery will exist only in the history books.

Freed villagers in Sakdouri, India | Photo: FTS/Middleberg

Let me close with the story of the village of Sakdouri. By sheer coincidence, the day after I visited the slave village I described for you, we went to a village named Sakdouri that had been liberated just one year earlier. Eighteen families – 52 people in all – had been enslaved in a brick-making factory. One of the men got word to a neighboring village that had already been liberated. They, in turn, contacted our local partner and our country director, who worked with the police to mount a raid on the factory. One year later, I met with them in a lovely new school they had built for the village children. They described what had happened in that year of freedom. The villagers were earning a living from farming, children were going to school, they were getting health care and new homes had been built. A paved road was coming to the village. Most importantly, they said: “We know what happened to us and why. We know how to protect ourselves. No one will ever make slaves of us again.”

More than that, they had become campaigners for freedom. They were going to surrounding villages and educating others about how to protect themselves.

So they told us their story and we got up to leave. But the villagers said: “No, no, no. You can’t leave yet. We have to sing you our freedom song.” So they took out their instruments and began to sing: “We know our rights. We keep our rights. We do not fear sticks or guns or slave owners. We will achieve our destiny.”

This is what we seek – to hear freedom’s song in every language – to know that the sad dirge of bondage is heard no more – and that the great chorus of liberation resounds to the heavens.