People who have been directly affected by a certain issue are the ones who best know its root causes, consequences, implications, and dynamics. They are also the ones who best know what the solutions to that issue may be. In virtue of their unique knowledge through lived experience, survivors should be at the heart of approaches to combat human trafficking. In fact, research has documented successful outcomes of survivor engagement in areas such as domestic violence, sexual abuse, and child soldiering.

However, in the anti-trafficking movement, engaging survivors is a practice that still suffers from a series of major limitations. This occurs mostly because survivors of human trafficking are still treated as helpless victims in search of assistance, as needy recipients of services, as lucky beneficiaries of the anti-slavery movement’s largesse, and as trauma-bearing individuals who are exclusively defined by their trauma.

Yet, in recent years, voices (and especially voices of survivor leaders themselves) have risen that criticize the dominant approach to survivor engagement and call for a substantial change throughout the movement. This change in discourse (and hopefully in direction) is important for two main reasons. First, anti-trafficking initiatives led by survivors have greater credibility with vulnerable individuals and communities, greater relevance, greater sustainability, and greater capacity to address the root causes of exploitation. Second, engaging survivors in an inclusive way can support survivors to acquire new skills, confidence and self-esteem, social inclusion, financial stability, professional development, and reduced vulnerability.

Building on these considerations, Fre the Slaves and Haart Kenya‘s research aimed to provide organizations in the anti-trafficking space with recommendations on practices of inclusive survivor engagement that may be standardized through an organization’s policy. To do so, it explored the survivor engagement practices of key counter-trafficking organizations (with a special focus on challenges that limit survivor engagement) and investigated the survivors’ own assessment of their participation in the anti-trafficking movement. Believing that discussions on survivor engagement need to be context-based, this research focuses specifically on Eastern and Central Africa – a region that is a source, route of transit, and destination for trafficked men, women, and children. However, the significance of this research certainly travels beyond East and Central Africa.

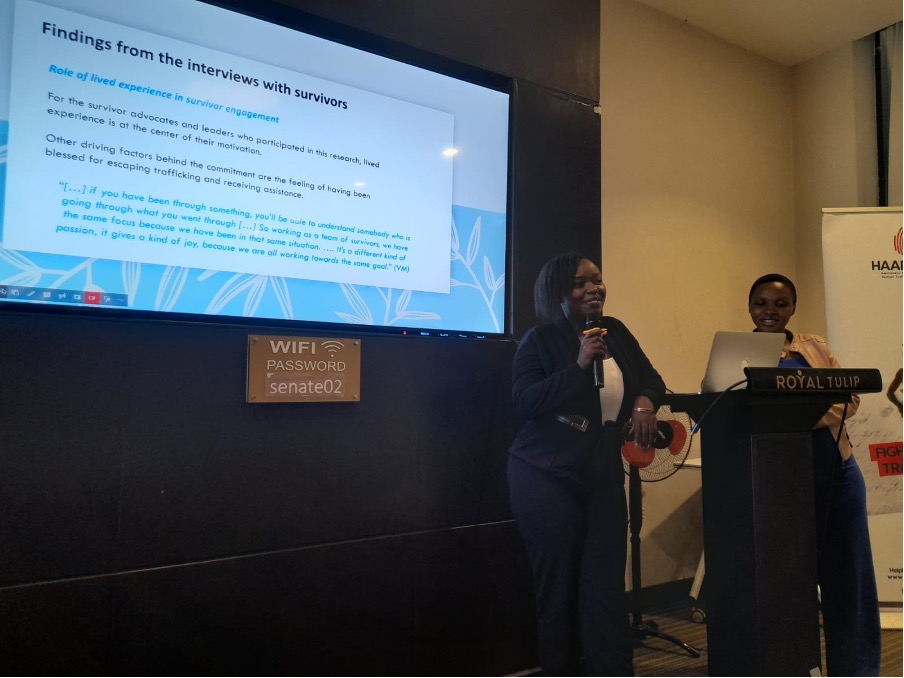

Using a mixed method approach, in this research FTS and HAART referred to the analysis of secondary sources, interviews with 18 survivors from Cameroon, DRC, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan, online surveys for organizations in East and Central Africa, and a validation workshop with survivors who participated in the research to collectively review the findings, discuss the recommendations, channel the perspectives of survivors into the final report, and minimize the risk that researchers would misinterpret the data.

From a methodological perspective, a distinctive contribution of this research was the active, multifaceted, and continuous participation of people with lived experience. On the one hand, survivors contributed as researchers. They underwent training in qualitative research skills and participated in conducting the interviews, analyzing the data, identifying key findings, and developing recommendations. On the other hand, survivors contributed as respondents, sharing their insights and perceptions regarding survivor engagement practices.

Building on the data collected over the course of several months, the research offers a series of recommendations to anti-trafficking organizations in East and Central Africa aimed at enhancing and deepening their approach to, and practices of, survivor engagement. While doing so, attention is given to organizational culture, survivor networks, finances and employment, capacity building, and security.

Some key recommendations for organizations include:

• Set a budget for survivor engagement

• Ensure that survivors and employees are trained on relevant issues (e.g., ethical storytelling and security

• Acknowledge and give room to the distinctive value of lived experience, but do not expect or limit survivors to sharing their personal experience

• Create multiple access for survivors to join the movement, also for those without prior engagement in social justice work

• Take in account individual needs (e.g., accommodation, translation, childcare, etc.) to enable full participation

• Keep mental health services for survivors accessible at all stages

• Avoid tokenism. Make sure you interact not only with individual survivor leaders and advocates, but with a community of survivors. Look for diverse perspectives

• On all occasions, consider whether a new opportunity can be given to survivors, and whether elements of survivor-to-survivor interactions can be included and supported

• Support survivor networks

• Remunerate survivor advocates and leaders adequately and sustainably for their engagement. Travel allowances are only the bare minimum. Consider this when budgeting for projects and proposals

• Reconsider job descriptions to reflect those qualifications that survivors possess. Create positions and job descriptions explicitly for survivor advocates or leaders

• Employ survivors and train them on the job to handle the assignments

• Offer and share learning and capacity-building opportunities. Those can also be opportunities by third parties, networking, and travel opportunities

• Offer mechanisms of training and professionalization like “shadowing” (teaming up a survivor advocate leader and an organizational staff member). Budget for this in proposals

• Actively support the willingness of survivors to combine their personal experience with a professional qualification of their choice to get their preferred position in the movement

• Make sure that survivor advocates and leaders are aware of the risks that are related to their counter-trafficking engagement

• Take measures to uphold security in different areas, including on social media and in media engagement, interactions with affected communities, and mitigate psychological consequences resulting from any interactions

This research was conducted as part of Free the Slaves research program. Visit our research page to learn more about why and how we conduct research.